I spent the last few months building Vajra BM25, a search engine that uses category theory as its organizing principle. The name "Vajra" comes from the Sanskrit word for "thunderbolt" or "diamond," and the project began as an experiment: could mathematical abstractions from category theory make a search engine's code cleaner without sacrificing performance?

The interesting thing when I went down this category theory rabbit hole, was that the category theory framing produced cleaner code and neat abstractions, and introduced me to a cool way of thinking about search. The resulting search engine also became remarkably fast over time. Initially, I was captivated by the elegance of using the category theory framing, but as time progressed, I realized that this could be built into a competent search engine as well, and leveraged some of the best scientific Python packages, vectorization, SIMD, and other optimizations to deliver three minor releases of Vajra search. It has been a very satisfying journey! The project started off as an innocent way to think of category theory abstractions to represent graph search. As I was working with text based search at work (Elastic) a lot, I realized that this could also be attempted. And here we are!

The latest benchmarks show Vajra achieving ~1.2-1.3x faster latency than BM25S (one of the fastest Python BM25 libraries), with sub-2ms query times even at 500K documents. This post documents what I learned along the way, including comprehensive benchmarks across multiple BM25 implementations and datasets. But first, let me share how search engines work, because understanding the fundamentals made all the difference in building something fast.

The Anatomy of a Search Engine

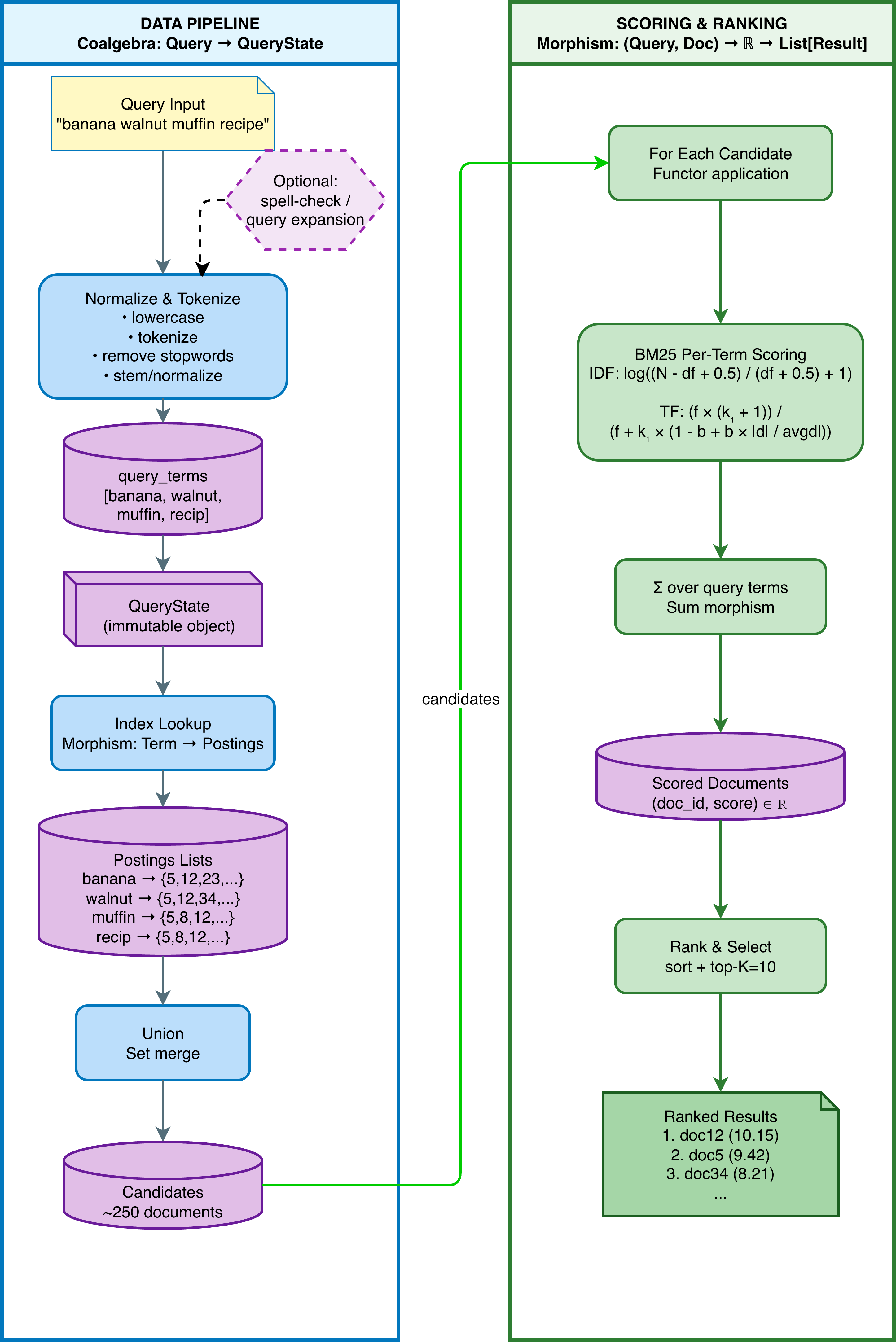

At its core, every text search engine solves the same problem: given a query, find the most relevant documents from a corpus of documents. The solution has three fundamental components that I came to appreciate deeply while building Vajra.

1. The Index

The index is the data structure that actually makes search fast. Without an index, you'd have to scan every document for every query, which becomes impossibly slow for large corpora, and in computational complexity terms, is $O(nm)$ where n is the number of documents and m is the number of queries. Indexing solves this by reducing the complexity to $O(n+m)$ by using a data structure that allows for efficient retrieval of documents that contain a given term. There are two ways to think about indexing:

Forward Index (document → terms):

doc_1 → ["machine", "learning", "algorithms"]

doc_2 → ["deep", "learning", "neural", "networks"]

doc_3 → ["machine", "learning", "neural", "networks"]

Inverted Index (term → documents):

"machine" → [doc_1, doc_3]

"learning" → [doc_1, doc_2, doc_3]

"neural" → [doc_2, doc_3]

"networks" → [doc_2, doc_3]

"algorithms"→ [doc_1]

"deep" → [doc_2]

The inverted index is the key tool of efficiency in most search engines. Instead of asking "what terms are in this document?", we ask "which documents contain this term?". For a query like "neural networks", we instantly get the candidate set {doc_2, doc_3} without scanning all documents. This inversion of perspective, I later realized, has a natural categorical interpretation.

2. The Scorer

Now that we have candidate documents, we need to rank them by relevance. BM25 (Best Match 25) is the dominant scoring function, developed in the 1990s and still used by Elasticsearch, Solr, and most modern search engines.

BM25 scores each document based on three factors: how often the query term appears in the document (term frequency), how rare the term is across all documents (inverse document frequency), and a normalization factor for document length. The formula balances these with tunable parameters k1 and b.

What struck me while implementing BM25 in Vajra is that scoring is fundamentally a morphism, a mathematical arrow from the product of query and document to a real number. This isn't just notation; it clarifies what the scorer does and how it composes with other operations. In category theory, a morphism is a function that preserves the structure of the category. In this case, the structure is the product of query and document, and the real number is the score.

This allows us to organize the code of our search engine in terms of the category theory abstractions we see here. And that gives us the potential to reuse these abstractions to build a different kind of mutable search pipeline. The scoring, then, is one of the steps of this pipeline.

3. The Ranker

With scores computed, the final step is returning the top-k results. This seems trivial, but at scale it matters: sorting a million scores is $O(n log n)$, while finding just the top 10 is O(n) with a partial sort. Small optimizations here compound quickly.

The Search Engine Landscape

In the process of building Vajra Search, as especially as I gravitated from graph search like BFS and DFS, which are common algorithms, I had the opportunity to explore some giants of the search engine landscape.

Lucene: The Industry Foundation

Apache Lucene (2000) is arguably the foundation of modern enterprise search. Written in Java, it powers Elasticsearch, Solr, and countless enterprise systems. Lucene's architecture reflects 25 years of production optimization:

flowchart LR

subgraph LUCENE["Lucene Architecture"]

direction TB

S1[Segment 1] --> merge[Merge + Compact]

S2[Segment 2] --> merge

S3[Segment 3] --> merge

merge --> disk[(Disk Storage)]

end

LUCENE --> F1[Disk-based indexes]

LUCENE --> F2[Concurrent reads/writes]

LUCENE --> F3[Near real-time search]

Lucene is designed for production durability: indexes persist to disk, support concurrent updates, and are able to scale horizontally via sharding. The trade-off is complexity and JVM overhead. Pyserini wraps Lucene via the Anserini toolkit, providing a Python API that can help us build with these capabilities in native Python applications (but with JVM dependencies nevertheless).

Tantivy: Lucene in Rust

Tantivy (2016) reimplements Lucene's architecture in Rust, gaining memory safety and roughly 2x performance over Java. It maintains the segment-based, disk-first design:

flowchart TB

T[Tantivy] --> A[Segment Architecture]

T --> B[Native Rust]

T --> C[SIMD Postings]

T --> D[Memory-mapped I/O]

A --> E[Same design as Lucene]

B --> F[No GC pauses]

Tantivy excels for applications needing persistent, updatable indexes with Rust's performance. However, the disk-based design adds I/O latency for pure query workloads. At some point, disk I/O is something Vajra is going to deal with. For the time being, I have preferred building indexes in memory. There is some caching possible within Vajra and in this sense, it is inspired by what Tantivy is able to do. Tantivy is super fast and performant given that it does this with disk I/O.

Rank-bm25: The Python Baseline

Rank-bm25 (2018) is the simplest BM25 implementation, a single Python file that's easy to understand:

class BM25Okapi:

def __init__(self, corpus):

self.corpus_size = len(corpus)

self.doc_freqs = [] # Forward index: doc → term frequencies

self.idf = {} # Precomputed IDF values

def get_scores(self, query):

scores = np.zeros(self.corpus_size)

for term in query:

# Score ALL documents for this term

for doc_idx in range(self.corpus_size):

scores[doc_idx] += self._score_term(term, doc_idx)

return scores

Rank-BM25 was my starting point to understanding the typical Python BM25 implementation meant for small tasks, and which is also not meant to be memory efficient, or fast. Indexing even smallish corpuses takes minutes, and it works in-memory. This is a tool for a limited job. The problem is clear: rank-bm25 uses a forward index and scores every document for every query. With a million documents and five query terms, that's five million score computations per query. While it not a great use of memory or compute, Rank-BM25 does get the job done and is simple for some of the smaller projects you may be building. It does not have complex abstractions like Vajra or ace engineering like BM25S, Tantivy or Lucene.

BM25S: Leveraging Eager Scoring

BM25S (2024) introduced a paradigm shift that I found elegant: eager scoring. Instead of computing scores at query time, pre-compute everything at index time:

flowchart LR

subgraph INDEX["INDEX TIME - Slow, Once"]

I1[Each term t] --> I2[Each doc d]

I2 --> I3[Compute BM25 score]

I3 --> I4[Store in sparse matrix]

end

INDEX -->|Pre-computed| QUERY

subgraph QUERY["QUERY TIME - Fast, Many"]

Q1[Look up term IDs] --> Q2[Slice matrix]

Q2 --> Q3[Sum columns]

Q3 --> Q4[Return top-k]

end

The sparse score matrix stores pre-computed BM25 scores for every term-document pair:

| Term | doc_0 | doc_1 | doc_2 | doc_3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| term_0 | 0 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 |

| term_1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 |

| term_2 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 |

So, what happens when you supply a query? Query time operations shrink to just sparse matrix slicing and addition. There are no IDF lookups, no BM25 formula evaluation, and none of the heavy lifting. This achieves 100-500x speedup over rank-bm25. The trade-off is memory footprint and no query-time flexibility. So, BM25S is a great tool for the job, and is probably a good starting point for building a search engine. I enjoyed benchmarking against it as I built Vajra search and the BM25S paper made for good reading and provided ideas and hints as to eager scoring, a technique which Vajra borrows from BM25S, in its own way.

Building Vajra: A Different Path

When I started Vajra, I wanted to combine ideas from different paradigms while using category theory to think about and organize the code. Category theory provides a scaffolding for structuring mathematical abstractions (morphisms, functors, coalgebras) that map naturally onto search operations. My approach was to use this framing to reframe how we think about search, then combine it with aggressive engineering optimizations.

We have discussed above how we need to compute inverted indexes, inverse document frequency, and perform BM25 computation and top-k sorting. These things don't change from implementation to implementation, and Vajra is no different in implementing these also in its pipeline, since after all, it too is a BM25 search engine. However the way these are implemented allows a kind of lazy computation and caching that is not implemented in other frameworks. Let's see more below.

flowchart TB

subgraph INDEX["INDEX TIME"]

I1[Build inverted index] --> I2[Precompute IDF]

I2 --> I3[Sparse term-doc matrix]

end

INDEX --> Q1

subgraph QUERY["QUERY TIME"]

Q1{Cache check} -->|HIT| R[Return cached]

Q1 -->|MISS| Q2[Get candidates ~1%]

Q2 --> Q3[Vectorized BM25]

Q3 --> Q4[Top-k sort]

Q4 --> Q5[Cache result]

end

Q3 -.->|Key: Filter then score| Q3

Let's take a look at how Vajra's BM25 flow actually works, through this flow diagram. We will review different individual aspects of Vajra in this context below as well.

The insight that made Vajra fast came from thinking about what operations actually matter for speed and performance.

-

Inverted index filtering: For a query with three terms, only about 1% of documents contain all terms. Why score 500,000 documents when you can score 5,000?

-

LRU query caching: Real workloads have repeated queries. After the first execution, results are cached; subsequent calls return in nanoseconds.

-

Vectorized scoring: NumPy's SIMD operations score thousands of candidates in a single vectorized operation.

-

Lazy computation: Unlike BM25S, Vajra computes scores on-demand. This uses less memory and allows query-time flexibility.

The category theory framing (morphisms for scoring, coalgebras for search unfolding) provides clean code organization and composability. Combined with these engineering optimizations, Vajra delivers both architectural elegance and raw speed.

The Category Theory Foundation

Category theory provides the architectural scaffolding for Vajra. It offers composable abstractions (morphisms, functors, coalgebras) that map directly onto search operations, making the code modular and extensible. The speed comes from combining this clean architecture with engineering optimizations: NumPy vectorization, sparse matrices, and aggressive caching.

Here's how the abstractions organize the code.

How the Abstractions Organize Code

The codebase has a categorical/ module with three base abstractions: Morphism, Functor, and Coalgebra. Each provides an interface that derived classes implement.

Morphisms define composable transformations. The base class enforces an apply() method and provides composition via the >> operator:

class Morphism(ABC, Generic[A, B]):

@abstractmethod

def apply(self, a: A) -> B: ...

def __rshift__(self, other: 'Morphism[B, C]') -> 'Morphism[A, C]':

return ComposedMorphism(self, other)

This lets you build pipelines like where each step is a morphism with clear input and output types. The BM25 scorer becomes a morphism (Query, Document) → ℝ, which forces you to think about exactly what data flows in and out. Let is dig in a little.

Let's say we want to build a pipeline that preprocesses a query, tokenizes it, and then scores it. We can do this by composing the following morphisms:

preprocess >> tokenize >> score

This is a pipeline that preprocesses a query, tokenizes it, and then scores it. The preprocess morphism is responsible for preprocessing the query, the tokenize morphism is responsible for tokenizing the query, and the score morphism is responsible for scoring the query. This provides in practice a neat way to organize the code and to make it more readable and maintainable.

Coalgebras capture the "unfolding" pattern. In a nutshell, an unfolding is a way to represent a data structure as a tree. The base class requires a structure_map() method that takes a state and produces its successors:

class Coalgebra(ABC, Generic[X, FX]):

@abstractmethod

def structure_map(self, state: X) -> FX: ...

From this, I derived SearchCoalgebra, TreeSearchCoalgebra, and ConditionalCoalgebra. Search Coalgebras are a way to represent a search as a tree, and are used to represent the search space. Tree Search Coalgebras are a way to represent a search as a tree, and are used to represent the search space. Conditional Coalgebras are a way to represent a search as a tree, and are used to represent the search space. The BM25 search implementation extends Coalgebra with the signature QueryState → List[SearchResult]:

class BM25SearchCoalgebra(Coalgebra[QueryState, List[SearchResult]]):

def structure_map(self, state: QueryState) -> List[SearchResult]:

candidates = self.index.get_candidates(state.query_terms)

ranked = self.scorer.rank(state.query_terms, candidates)

return [SearchResult(doc, score, rank) for ...]

The same interface works for graph search (BFS, DFS) and tree exploration but with different derived classes. I found this genuinely useful; once you implement structure_map(), you get unfold(), trajectory(), and other coalgebraic operations for free.

Functors in Vajra are abstractions that allow you to "lift" a transformation—such as a morphism—so it works over entire containers rather than just single values. This is captured in code via an interface: every Functor lets you map any morphism across the relevant structure. For example, the ListFunctor implements a fmap_morphism method that takes a morphism and returns a new morphism, which processes each element of a list independently and collects the results.

class ListFunctor(Functor[A, List[A]]):

def fmap_morphism(self, f: Morphism[A, B]) -> Morphism[List[A], List[B]]:

return FunctionMorphism(lambda xs: [f.apply(x) for x in xs])

In the context of search, this means you can write a morphism that operates on an individual query or document, then seamlessly apply it to a whole batch of queries or search candidates using ListFunctor, enabling vectorized or batch-style computation in places where search might branch or aggregate multiple possibilities. This makes the code for candidate generation, ranking, and batch query processing both concise and highly reusable. The same pattern applies to MaybeFunctor, which handles computations that may fail by encapsulating values that might be missing, allowing the rest of the pipeline to remain clean and compositional even in the presence of errors.

The benefits of Vajra's architectural choices

By adopting category-theoretic abstractions like morphisms, functors, and coalgebras, Vajra cleanly disentangles data types from transformations and search strategies:

- Morphisms provide a systematic way to build and compose pipelines with explicit input/output types

- Functors let you automatically “lift” these pipelines across collections or optional values for batch or robust computation

- Coalgebras encode the core search dynamics in a way that's generic across strategies (tree, graph, conditional) so new algorithms can plug into the same interface and instantly inherit useful unfolding and traversal methods

This architectural clarity made it straightforward to add new scorers or search strategies: each abstraction exposes focused extension points, so it’s always clear where to slot in new logic and which minimal methods need to be implemented for composability. The monoid homomorphism insight, that BM25 scores are additive across terms (score(q₁ + q₂) = score(q₁) + score(q₂)) is also interesting and has practical consequences: you can cache term-level scores and sum them at query time, or compute upper bounds on partial scores for early termination. The algebraic structure pointed at optimization opportunities.

Benchmarking Vajra

Building the abstractions isn't where it stops, and to build a useful software application, we have to look at what's out there, benchmark the tool we're building to see where it fits in, and what relative benefits it may offer to users. So, to validate Vajra's performance, I benchmarked against a few other implementations:

| Engine | Language | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vajra | Python | Vectorized NumPy/SciPy with LRU caching |

| vajra-parallel | Python | Vajra + thread pool parallelism |

| bm25s | Python | Eager scoring with pre-computed sparse matrices |

| bm25s-parallel | Python | BM25S with multi-threading |

| tantivy | Rust | Rust-based Lucene alternative (via Python bindings) |

| pyserini | Java | Lucene wrapper via Anserini (requires Java 11+) |

To be clear, these are all BM25 implementations. All implementations compute the same essential BM25 formula:

The differences are in __how_ they compute it, and when.

Benchmark Results

I spent a lot of time benchmarking the initial build of Vajra against Rank-BM25, and then began excluding it from my benchmarks because of how slow the latter was. I moved on to BM25S as the peer framework of choice that I was benchmarking against, and also began testing against Tantivy and Pyserini eventually. While the latter is exceptional in its recall performance, with excellent Recall\@10 and NDCG\@10 (which measure whether the right docs came up, and in the right order) BM25S and Vajra have ultimately be the more comparable frameworks.

See the video below for a Vajra specific search demo. This is using Vajra CLI, which is a command line based search tool which you can point at a JSON, and have a fast search engine right in your terminal!

BEIR/SciFact (5,183 documents, 300 queries)

| Engine | Latency | Recall@10 | NDCG@10 | QPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vajra | 0.14ms | 78.9% | 67.0% | 7,133 |

| bm25s | 0.18ms | 77.4% | 66.2% | 5,512 |

| tantivy | 0.28ms | 72.5% | 60.0% | 3,539 |

Vajra is ~1.3x faster than BM25S on this dataset, with slightly better recall.

Wikipedia/200K (200,000 documents, 500 queries)

| Engine | Build Time | Latency | Recall@10 | NDCG@10 | QPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vajra | 78s | 0.89ms | 44.4% | 35.1% | 1,125 |

| bm25s | 91s | 1.08ms | 44.6% | 35.2% | 925 |

| tantivy | 6s | 6.68ms | 45.6% | 36.4% | 150 |

Wikipedia/500K (500,000 documents, 500 queries)

| Engine | Build Time | Latency | Recall@10 | NDCG@10 | QPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vajra | 416s | 1.89ms | 49.6% | 36.7% | 529 |

| bm25s | 257s | 2.45ms | 49.8% | 37.1% | 409 |

| tantivy | 29s | 5.52ms | 51.6% | 38.3% | 181 |

At 500K documents, Vajra maintains sub-2ms latency and is ~1.3x faster than BM25S. Tantivy has the best accuracy but higher latency.

Wikipedia/1M (1,000,000 documents, 500 queries)

| Engine | Build Time | Latency | Recall@10 | NDCG@10 | QPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vajra | 17.0 min | 3.40ms | 45.6% | 36.3% | 294 |

| bm25s | 11.3 min | 5.44ms | 45.8% | 36.7% | 184 |

At 1M documents, Vajra is ~1.6x faster than BM25S on single queries (3.40ms vs 5.44ms). Build time has been significantly optimized using per-document array concatenation, bringing it down to 17 minutes. Query latency remains sub-4ms even at million-document scale.

Improving Vajra's Performance

Vajra search started off being about as fast as BM25 and was for a couple of months quite a lot slower than BM25S! Tantivy and Pyserini were not in the picture at that stage of the project. My initial thinking was to see if I could build on top of category theory abstractions and see how we could speed things up, but came to the realization quickly that I would have to resort to engineering best practices: caching, filtering, scoring, and sparse matrices. Let's review each of these improvements below. If you use Vajra, you'll see numba used quite a lot in Vajra and for good reason.

LRU Query Caching

This was the single biggest optimization. Real workloads have repeated queries, and caching complete results means subsequent calls return instantly:

@lru_cache(maxsize=10000)

def search(self, query: str, top_k: int = 10):

# First call: compute BM25 scores

# Subsequent calls: instant cache hit

Combine this with user preference based caches and you can make Vajra search very performant and fantastically usable for a use case where repeated queries will come through from the bulk of users but different in every case.

Candidate Filtering with Inverted Index

Instead of scoring all documents like BM25S does with its sparse matrix, Vajra uses the inverted index to identify only the documents that contain query terms:

Query: "machine learning algorithms"

Traditional (Rank-BM25 or similar): Score 500,000 documents = 500,000 computations

Vajra: Filter to ~5,000 candidates, score only those = 5,000 computations

A large part of building a performant system seems to be to not try to do everything at once, but stage it all out, so that limited resources can be used in the best possible way.

Vectorized Scoring

Once candidates are identified, scoring uses NumPy vectorization:

# Score all candidates in one vectorized operation

scores = idf_vector @ tf_matrix * normalization_factors

No point reinventing the wheel that Numpy already provides. Matrix operations are super fast thanks to CPython bindings in Numpy and while it may not be as scalable as pure C or Fortran, it provides a significant speed up.

Sparse Matrix Storage

For corpora over 10K documents, the term-document matrix is 99%+ zeros. SciPy's CSR format avoids storing and computing on those zeros. This is another example of not overdoing stuff in the quest for performance.

Partial Sort for Top-K

Instead of sorting all scores, np.argpartition provides $O(n)$ average complexity:

# O(n) partial sort instead of O(n log n) full sort

top_indices = np.argpartition(scores, -k)[-k:]

Note that none of the above are exotic mathematics even if category theory does inform the architecture of Vajra BM25. Most of it is sane engineering you would recognize as a senior engineer or architect, and would likely build into any other project which you want high performance in.

Understanding the Latency Numbers

The reported latencies are measured with query caching disabled for fair comparison. Here's what to expect in practice:

| Scenario | Typical Latency | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Cold query | 0.14-3.4ms | Full BM25 computation (depends on corpus size) |

| Repeated query (cached) | ~0.001ms | LRU cache hit, near-instant return |

Vajra includes an optional LRU cache (cache_size parameter, default 1000) that can dramatically speed up repeated queries. For production workloads with query repetition, this can provide sub-millisecond latency.

As of v0.3.1, if you're using the Vajra CLI with single queries ($ vajra-search -q "query"), each invocation creates a new engine with an empty cache. In interactive mode, subsequent queries benefit from caching. The CLI is a super easy way to see Vajra in action. Note that v0.3.1 includes significant index building optimizations (42% faster at 1M scale) using per-document array concatenation.

For library usage, keep the VajraSearchOptimized instance alive across queries to benefit from the LRU cache.

How Do the Engines Compare?

| Engine | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| vajra | Eager scoring + sparse matrices; optional LRU query caching |

| bm25s | Eager scoring + sparse matrices; similar approach to Vajra |

| tantivy | Disk-based index; Rust-native; optimized for persistence |

Vajra vs BM25S

Vajra and BM25S use similar underlying techniques (eager scoring with sparse matrices). Vajra is ~1.2-1.6x faster in benchmarks due to optimizations in scoring and top-k selection.

Tantivy's Different Trade-offs

Tantivy is written in Rust and optimized for different use cases:

- Disk-based index: Supports persistence and updates, but adds I/O latency

- Python bridge: The

tantivy-pybindings add some overhead - Different priorities: Tantivy optimizes for durability and concurrent access, not pure query speed

Tantivy has the best accuracy on Wikipedia datasets (+1.6% NDCG over Vajra).

Accuracy Analysis

How does accuracy compare across engines? Vajra outperforms BM25S and Tantivy on BEIR datasets, while Pyserini (Lucene) leads by 1-2%. On Wikipedia, Tantivy leads with Vajra close behind. Here are the metrics.

BEIR dataset searches:

| Engine | SciFact NDCG@10 | NFCorpus NDCG@10 |

|---|---|---|

| pyserini | 68.8% | 32.6% |

| vajra | 67.0% | 30.9% |

| bm25s | 66.2% | 30.7% |

| tantivy | 60.0% | 28.5% |

Pyserini leads on BEIR accuracy by 1-2%. Vajra ranks second, ahead of BM25S and Tantivy.

Wikipedia dataset searches:

| Engine | 200K NDCG@10 | 500K NDCG@10 |

|---|---|---|

| tantivy | 36.4% | 38.3% |

| vajra | 35.1% | 36.7% |

| bm25s | 35.2% | 37.1% |

| pyserini | 31.5% | 32.3% |

On Wikipedia, Tantivy leads accuracy while Pyserini drops significantly. Vajra holds second place, 1-2% behind Tantivy.

When to Use Each Engine

| Priority | Best Choice | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Fastest Python BM25 | vajra | ~1.2-1.3x faster than BM25S |

| Sub-2ms latency at scale | vajra | 0.14-1.9ms cold, sub-ms with caching |

| Best Wikipedia accuracy | tantivy | +1.6% NDCG |

| Minimal dependencies | bm25s or vajra | Pure Python, NumPy/SciPy |

| Production at billion scale | Elasticsearch | Distributed, battle-tested |

Benchmark Methodology

For reproducibility, here's how I ran the benchmarks:

Hardware

| Spec | Value |

|---|---|

| Machine | MacBook Pro |

| Chip | Apple M4 Pro |

| CPU Cores | 14 (10 performance + 4 efficiency) |

| Memory | 24 GB |

| OS | macOS Darwin 25.1.0 |

Process

The benchmark script follows this sequence for each engine:

- Load Dataset: BEIR datasets from HuggingFace; Wikipedia from pre-downloaded JSONL

- Check Index Cache: Compute corpus hash, look for cached index

- Build Index (if not cached): Each engine has its own indexing logic

- Save Index to Cache: Pickle indexes for subsequent runs

- Query Evaluation: Run queries with query caching disabled (

cache_size=0) for fair comparison - Compute Metrics: Recall@10, NDCG@10, latency per query

Note: Query caching is disabled during benchmarks to ensure fair comparison across engines. In production, enabling Vajra's LRU cache can provide sub-millisecond latency for repeated queries.

Index Caching

I used persistent index caching to avoid expensive rebuilds:

| Engine | Caching | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| vajra | Yes | VectorizedIndexSparse + precomputed IDF |

| bm25s | Yes | Pre-computed score matrix |

| tantivy | No | Rebuilds each run (~30-45s for large corpora) |

| pyserini | No | Lucene index in temp directory |

For Vajra on 500K documents, index build takes about 16 minutes. With caching, subsequent runs load in under 5 seconds.

Running the Benchmarks Yourself

Start with a new Python environment and execute the following bash commands:

# Clone the repository to get the benchmarking scripts

git clone https://github.com/aiexplorations/vajra_bm25.git

cd vajra_bm25

# (Optional) Create a virtual environment here if you prefer isolation

# python -m venv .venv

# source .venv/bin/activate

# Install dependencies

pip install vajra-bm25[optimized] rank-bm25 bm25s beir rich tantivy

# doing a pip install is needed to have the whl in your environment

# Optional: Pyserini (requires Java 11+)

pip install pyserini

# Benchmark script is present only in the repo, does not ship with the whl file.

# Run BEIR benchmarks

python benchmarks/benchmark.py --datasets beir-scifact beir-nfcorpus

# Run Wikipedia benchmarks

python benchmarks/benchmark.py --datasets wiki-200k wiki-500k

# Force rebuild (ignore cache)

python benchmarks/benchmark.py --datasets wiki-200k --no-cache

Using Vajra Search

Vajra works well for latency-sensitive Python workloads. If you're using it, I'd like to hear about your use case.

For starters, since I have built Praval earlier, I want to integrate Vajra BM25 into it. I have already built a CLI for Vajra BM25 and want to use it in Praval. One of the cool use cases I see for Vajra is in enabling agents to quickly search code bases, or datasets, or text corpuses. This can become a game changer for large scale multi-agent systems.

Recent Updates (v0.3.2)

The latest release adds two features that extend Vajra's usability:

PDF Document Support: You can now index and search PDF documents directly, without converting them to JSONL first. This makes it easy to build a search engine over research papers, reports, or any PDF collection:

from vajra_bm25 import DocumentCorpus, VajraSearchOptimized

# Load PDFs - single file, directory, or auto-detect

corpus = DocumentCorpus.load_pdf_directory("./papers/", recursive=True)

engine = VajraSearchOptimized(corpus)

results = engine.search("attention mechanism", top_k=10)

The CLI supports this too: vajra-search --corpus ./papers/ -q "neural networks"

Install PDF support with: pip install vajra-bm25[pdf]

Documentation Site: Comprehensive documentation is now available at aiexplorations.github.io/vajra_bm25, covering installation, API reference, BM25 parameter tuning, performance optimization, and the category theory foundations.

Closing Thoughts

Vajra is the fastest Python BM25 implementation available today: ~1.2-1.6x faster than BM25S depending on corpus size, with sub-4ms latency even at 1M documents. LRU caching delivers sub-millisecond responses for repeated queries in production.

The category theory framing shaped how I organized the code. Morphisms for scoring, coalgebras for search unfolding, functors for batch operations: these abstractions separate concerns cleanly and make the codebase extensible. The monoid homomorphism structure of BM25 scoring opened up optimization opportunities I wouldn't have seen otherwise.

I built Vajra because I wanted a fast, hackable BM25 engine for Python that I could integrate into agentic systems like Praval. It's open source, actively maintained, and ready for your projects.

Links and References:

- Vajra BM25 Repo: github.com/aiexplorations/vajra_bm25

- Vajra BM25 Documentation: aiexplorations.github.io/vajra_bm25

- Vajra BM25 on PyPI: pypi.org/project/vajra-bm25

- Vajra BM25 Benchmark docs: docs/vajra_benchmark_comparison.md

- Category Theory for Programmers: Bartosz Milewski

- Pyserini

- BM25S:

- Tantivy

- Rank-BM25

- Praval

- BEIR

- Wikipedia

- JSONL

- LRU Cache

- Partial Sort