The current frontier of AI is dominated by powerful deep learning systems: large language models, generative AI, AI agents, and software-defined workflows that compose them. But it wasn't always like this—and perhaps it shouldn't always be.

Introduction

Like many senior data science professionals, I began my journey by getting my hands dirty with data preparation, cleaning, modeling, and statistical analysis. While my recent years have been about building LLM-based applications and ML systems at scale, I recently found myself drawn back to the basics. I picked up Foundations of Data Science by Blum, Hopcroft, and Kannan — a book I've owned in both digital and print form — and began reading it in earnest.

My own copy of this book is from Hindustan Book Agency, and comes with a nice Sanskrit quote at the back:

यथा शिखा मयूराणां नागानां मणये यथा |

तथा वेदाङ्गशास्त्राणां गणितं मूर्धनि स्थिथम् ||

Rough translation: "Mathematics is at the pinnacle of all science and knowledge, as the crest of a peacock or the hood of a serpent is at their very helm".

To my surprise (and mild dismay), I was hooked. The first few chapters dive into high-dimensional geometry and fundamental theorems that shape our understanding of data — well beyond the "intro to ML" tutorials that unfortunately dominate the web. And that's exactly why they're valuable.

A Personal Lament

I sometimes lament that today's data science talent often bypasses foundational understanding. But I remind myself: even I didn't learn linear models or time series forecasting in the abstract. What matters, in the end, is role effectiveness.

Yet there's a catch. The tools we use today — powerful though they are — often mask the need for deeper understanding. They let us skip steps. That's great for productivity, but not always for intellectual clarity. And the more we try to build general intelligence on top of systems we don't deeply understand, the more fragile our edifice becomes. Like that person in Nebraska thanklessly maintaining a key component of the world's digital infrastructure.

This is why revisiting the foundations matters… not to gatekeep, but to ground.

Higher Dimensional Spaces, Law of Large Numbers and the Johnson-Lindenstrauss Lemma

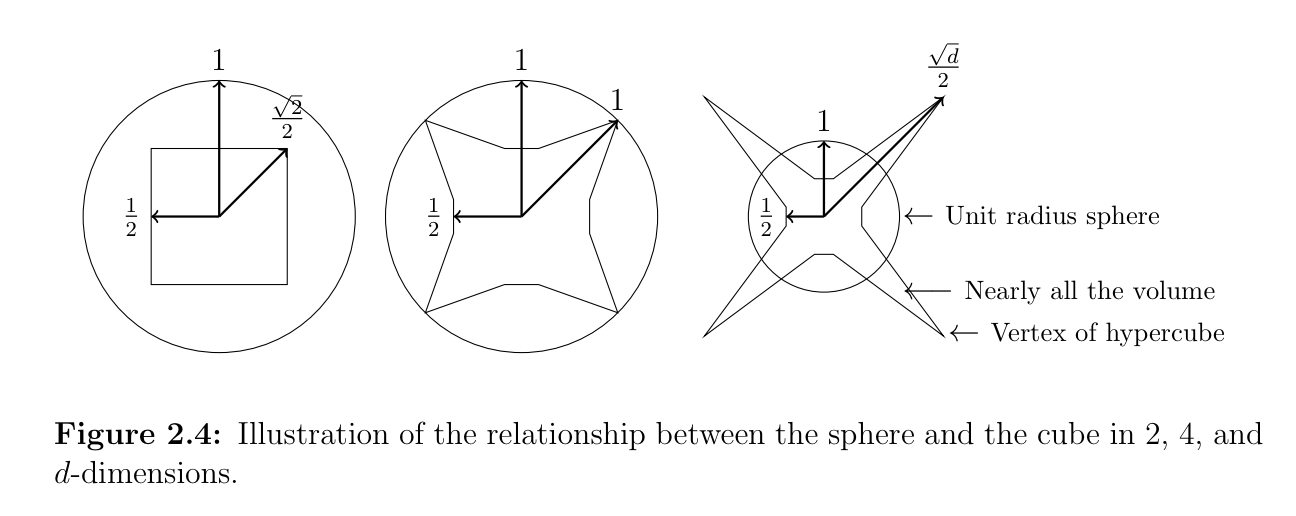

In Chapter 2 of Foundations of Data Science, we begin with geometric intuitions of high-dimensional space. A key insight: as dimensionality increases, our geometric intuitions break down.

- In 2D, a circle neatly encloses a square.

- In 3D, a sphere begins to diverge from the cube.

- In higher dimensions, most of the volume of a hypercube lies far away from the origin — the corners become "extreme."

- The unit ball, on the other hand, collapses toward the surface — most of its volume concentrates in a thin shell near its boundary.

This is one of many surprising results: in high dimensions, most of a sphere's volume lies near the surface. This affects how we think about distances, density, and similarity in models that live in high-dimensional space — like embeddings and feature vectors.

In two dimensions, a circle kind of "encloses" a square, and the square fits neatly inside. In three dimensions, the cube and the sphere have a more complex relationship, but the cube's corners still touch the sphere. But as you move into even higher dimensions, something quite surprising happens: the corners of the "cube" extend far beyond the sphere. It means that most of the cube's volume or "space" actually moves away from the center, and the sphere starts to feel "smaller" compared to the cube.

Another fun quirk is that in higher dimensions, the corners of shapes, like the vertices of a cube, become more "extreme" in the sense that they move farther away from the center. This leads to a lot of interesting results in data science and machine learning, where high-dimensional spaces can cause phenomena like the "curse of dimensionality."

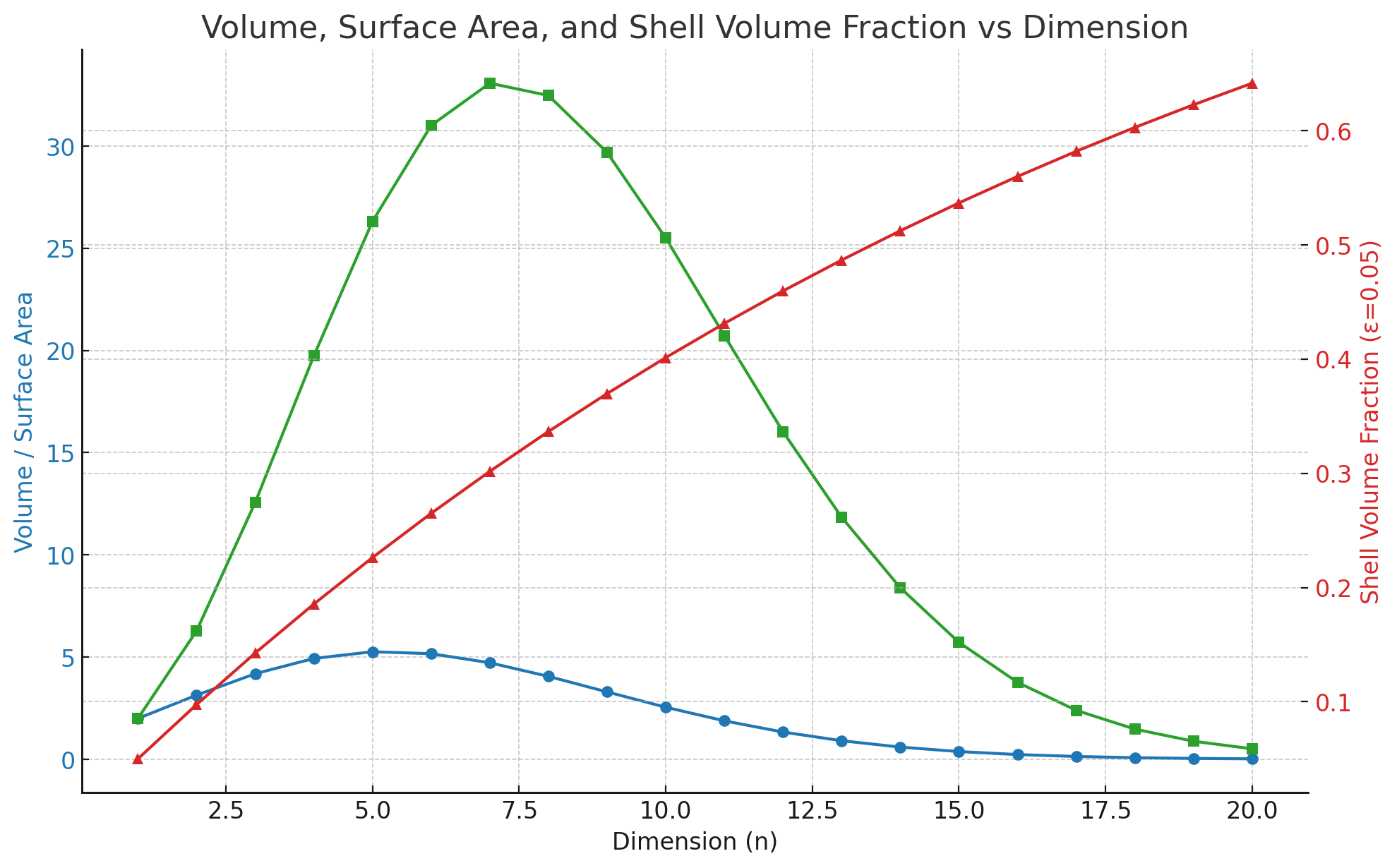

An interesting property, as the book says, of most higher dimensional objects, is that most of their volume is near the surface.

Key observations:

- Blue curve: Volume of the unit n-ball, which peaks and then declines.

- Green curve: Surface area of the unit ball, which also peaks then declines.

- Red curve: Fraction of the volume in a thin shell of thickness ε = 0.05, which increases steadily with dimension.

The geometric interpretation of this is intuitive and interesting and easier to grok, compared to the analytical methods described in the book. But the analytical method is elegant. We know from observation that a ball in 1D is just a line, there is no surface as such. In 2D, most of the area of the 2D unit ball (circle) is not close to the edge (circumference) of the unit ball – we can confirm this by computing an annulus. The thicker the annulus, the more the volume it would hold – and we see that a large part of the volume is still within the bulk of the circle.

In 3D, we begin to see how the surface area is vast for a sphere, and a thin shell near the surface can contain a considerable fraction of the volume. In fact, nearly 27% of the volume of a sphere is within 10% of the radius from the surface.

From Geometry to Modeling: Johnson–Lindenstrauss Lemma

Now let us turn our attention to the Johnson–Lindenstrauss Lemma — one of the elegant results in this chapter of the book, and evidently quite foundational to everything from dimensionality reduction to distance-preserving embeddings.

The JL lemma guarantees that a set of points in high-dimensional space can be projected into a lower-dimensional space (e.g., from 1000D to 100D) in such a way that the pairwise distances between points are approximately preserved. This is enormously useful when:

- You want to reduce the cost of computing distances or similarities

- You're working with text embeddings, sensor data, or image vectors

- You're designing algorithms like k-means, k-NN, or t-SNE

In other words, the JL Lemma gives mathematical backing to a hunch many of us have had in practice: you can project large feature spaces to smaller ones and still retain their structure — at least approximately.

It's not just theory; it's the backbone of algorithms in search, recommendation, and clustering.

Why This Matters Today

Most of today's AI is built on embeddings — text, image, graph, or otherwise. But how often do we examine the geometry of those embeddings? Or the distance metrics we use on them? Or how projection, rotation, or compression affects their behavior?

We've layered abstractions upon abstractions and now, we may be due for a reckoning.

What's Next: A Deeper Reckoning

Where does the JL Lemma lead us? Perhaps to a philosophy for better and more grounded, more interpretable, efficient AI systems.

Topics to explore:

- Random Projections and Applications

- Sparse random projections in NLP and search

-

Practical implementation tricks

-

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and SVD

- Geometry of best-fit subspaces

-

Low-rank approximations and latent structure

-

Manifold Learning & Dimensionality Reduction

-

Why techniques like Isomap, t-SNE, UMAP work (and when they don't)

-

KL Divergence, Mahalanobis Distance & Metric Spaces

- What makes a "good" distance in high dimensions?

-

When cosine similarity fails

-

Information Geometry

- Connecting probabilistic models to geometric intuition

-

Fisher Information and curvature

-

Compression and Representation

- What does it mean to "compress" data meaningfully?

- Trade-offs between compression, reconstruction, and learning

Parting Thoughts

Mathematics, as the Sanskrit verse on the back of the book says, is at the crown of all knowledge. And the deeper I go into data science, the more I realize this wasn't hyperbole. The more we understand the shape of our data, the more responsible we can be with the power of our models.

Maybe it's time to ground the frontier in the foundation again.