Over the last weekend I built out a service called "Sangraha" (which means "collection" in Sanskrit), which supports a large throughput and relatively low latency of data operations.

Sangraha's Architecture

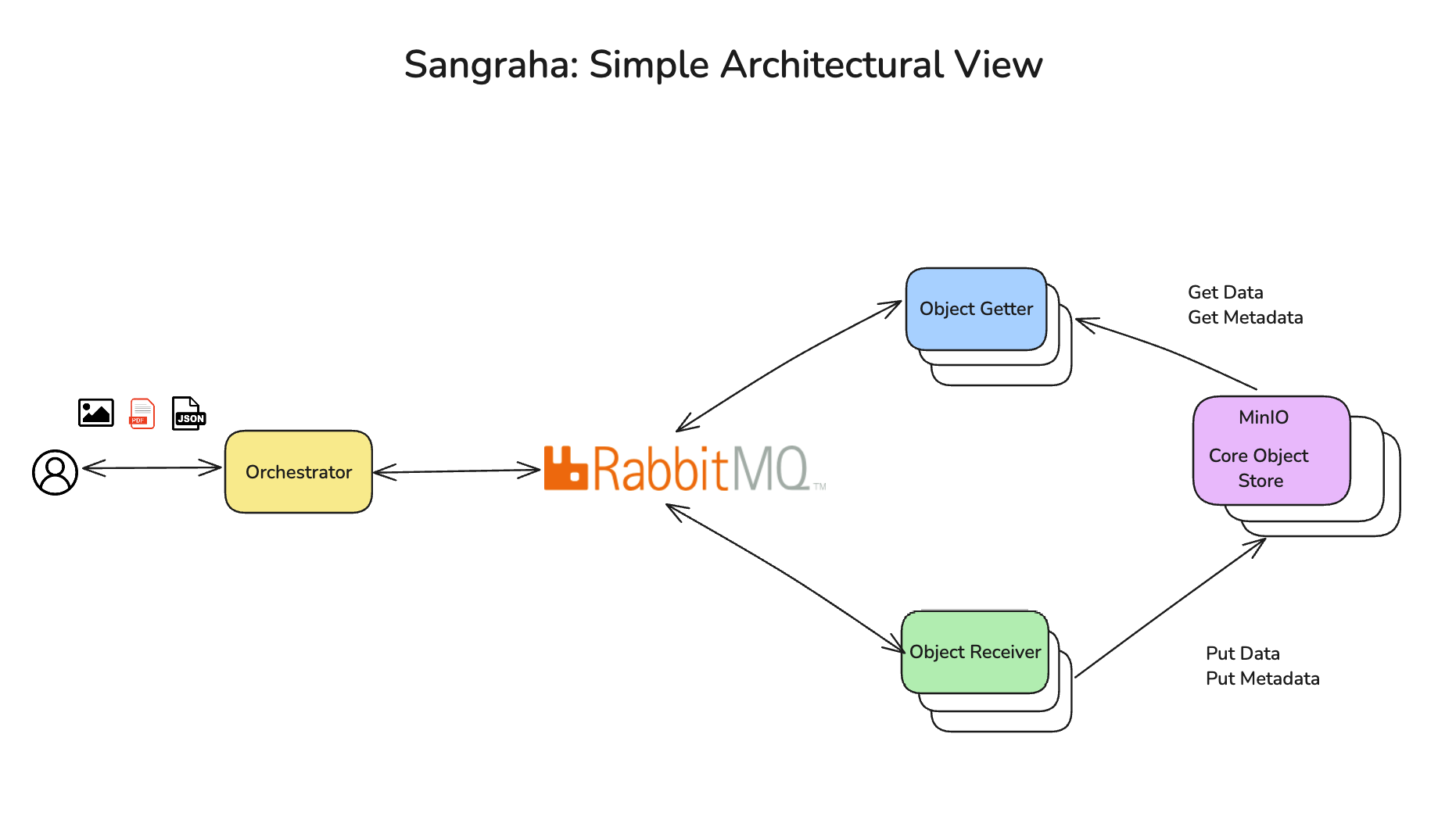

The overall architecture of Sangraha allows for a single orchestrator to use RabbitMQ for fast message based writes and reads from an object store. MinIO is the object store I've used in the backend. It is a production grade object store and is full featured, being S3 compatible. A couple of services – the object getter and object receiver are used for the get functionality and the put functionality respectively – the big take away here being that they are replicated and redundant, and provide scale through a Docker Swarm implementation. Another important takeaway is just the decoupling between the orchestrator and the actual write operation. The presence of multiple replicates and a loosely coupled architecture with a message queue really amps up the performance.

Some details of the current microservices based architecture are as follows:

- The orchestrator service is responsible for managing the services and ensuring that they are running and healthy.

- The object receiver service is responsible for receiving objects from the client and storing them in MinIO.

- The object getter service is responsible for retrieving objects from MinIO, and returning them to the client.

- Docker Swarm Mode is used to orchestrate the services and ensure that all components are running and healthy.

- A local registry is used to store the Docker images for the services.

- Start and stop scripts are provided to start and stop the services and clean up the Docker resources.

- A test script is provided to test the system's performance and scalability.

Testing Sangraha's Throughput

One of the more interesting things about building this service was to test out how well the service scales to different sizes of workloads and different rates. In effect, this was a load test. A number of cases were performed with some of the following results:

$ python src/test/test.py 100 20 --size 2048 --debug

Script initialized

2024-10-28 02:14:01,463 - INFO - Starting load test with 100 total requests

2024-10-28 02:14:01,463 - INFO - Using 8 processes for concurrent execution

2024-10-28 02:14:01,463 - INFO - Request size: ~2048 bytes

2024-10-28 02:14:03,212 - INFO - ----- Test Complete -----

2024-10-28 02:14:03,213 - INFO - Completed 100 requests, 100 successful

2024-10-28 02:14:03,213 - INFO - Total time: 1.75 seconds

2024-10-28 02:14:03,214 - INFO - Average rate: 57.16 requests/second

2024-10-28 02:14:03,214 - INFO - Total data transferred: 200.00 KB

2024-10-28 02:14:03,214 - INFO - Data throughput: 114.33 KB/second

Script completed

The above test was for 20 concurrent requests at a time, 100 total – and this was completed in 1.75 seconds, at a rate of 57.16 requests/second, which is a decent request rate for this kind of Docker Swarm based application. With Kubernetes scaling, potentially more requests could be handled.

However, beyond a point, MinIO in distributed fashion would need network overhead to synchronize nodes and maintain consistency. The network overhead would in fact make the storage service less performant. An example with five MinIO nodes below:

$ python src/test/test.py 100 20 --size 1048576 --debug

Script initialized

2024-10-28 02:35:44,745 - INFO - Starting load test with 100 total requests

2024-10-28 02:35:44,745 - INFO - Using 8 processes for concurrent execution

2024-10-28 02:35:44,745 - INFO - Request size: ~1048576 bytes

2024-10-28 02:35:44,754 - INFO - Operation mode: create

2024-10-28 02:35:57,748 - INFO - ----- Test Complete -----

2024-10-28 02:35:57,749 - INFO - Completed 100 requests, 100 successful

2024-10-28 02:35:57,749 - INFO - Total time: 12.99 seconds

2024-10-28 02:35:57,749 - INFO - Average rate: 7.70 requests/second

2024-10-28 02:35:57,749 - INFO - Total data transferred: 102400.00 KB

2024-10-28 02:35:57,749 - INFO - Data throughput: 7880.75 KB/second

Script completed

Observe how the requests/second dropped drastically with a larger cluster of MinIO nodes, because of the network traffic overhead. Perhaps this is illustrative of the performance of some distributed systems. Eventual consistency is the norm the more distributed a system gets, unless special mechanisms ensure faster consistency.

Concluding Remarks and Further Work

The most enlightening aspect of developing this application wasn't the architecture, but rather the testing phase. It highlighted the challenges networked distributed systems encounter with slowdowns and bottlenecks, which arise solely from scaling and the velocity of data in transit. Increasing the network scale leads to enhanced performance in the object store's write and read operations.

Considering Kubernetes for building a version of this might be a strategic move to manage state and establish a predictable capacity for an object store service like this. It's an exciting prospect for my upcoming experiments.

Envisioning Sangraha's components as compact, scalable microservices is on my mind, allowing for seamless scalability across various use cases. The insights gained here will undoubtedly be beneficial!